English learner population is growing, but bilingual education options are scarce

By Meg McIntyre, Granite State News Collaborative

All photos by Allegra Boverman, for Granite State News Collaborative

When LiQin Hong's family first moved to Peterborough, she was nervous about sending her daughter to school. As a Chinese immigrant, Hong wasn't yet proficient enough in English to help with homework and class assignments.

"She speaks Chinese at home, and when she [went] to school I was really worried about her English. I thought about looking for an ESL teacher for her," said Hong, whose daughter attends Peterborough Elementary School. "But after she [went] to school, she didn't need the ESL teacher, because now she speaks very good English."

At the same time, Hong, who is studying English at Keene Community Education, didn't want her daughter to lose her skills in Chinese. One of her classmates, Keene resident Vidhya Sreenath, had a similar experience when her son started kindergarten at Franklin Elementary School. She wondered if her family should change how they communicated at home to encourage her son's English development.

"We also tried to talk in English at home so that he can learn quickly, but the teacher there, he said, 'No, you just go with your language — we will teach him,'" Sreenath, who is from India, said. "'He needs to be very good at his mother tongue.'"

Striking this delicate balance between acquiring a new language and maintaining the first can be a challenge. That's because immigrant children are vulnerable to language attrition — the loss of fluency in one's native tongue — especially if they are completely immersed in a new language. It's estimated that this shift can occur within about three generations.

One model of English language instruction could help stem this type of language loss. The approach, called dual-language immersion, delivers content both in English and in a students' first language, with the goal of promoting biliteracy and allowing students to stay connected to their linguistic heritage.

In other states, dual-language immersion programs have become more common in recent years as the country grows increasingly diverse. The concept is considered one of the most effective instructional methods for English learners (ELs), but these schools are also attractive to parents who want to expose their English-speaking children to different languages and cultures.

In a two-way dual-language program, about half of students are typically native English speakers, while the other half speak the "target" language — such as Spanish — at home. Starting in kindergarten, classes are co-taught or taught by a bilingual educator, with the amount of instruction in each language varying by grade level.

Outcomes for EL students have historically lagged behind their native English-speaking peers. In 2018-19, the four-year graduation rate for English learners in New Hampshire was about 60%, according to the state education department, well below the statewide average of nearly 88%. That year, about 24% of ELs reached proficiency in English language arts, compared to 56% of students overall. About 22% of ELs scored proficient in math and 12% scored proficient in science, while 48% and 39%, respectively, of students overall reached that benchmark.

But there's evidence that dual-language immersion could be a helpful strategy to bridge these gaps. One study from 2017 found that students selected for a lottery-based immersion program scored higher on standardized reading assessments than students who didn't win a spot in the immersion program. The study also indicated that being enrolled in an immersion program did not negatively impact students' math and science scores.

Researchers also link bilingual education to a range of potential cognitive benefits, such as improved attention, greater empathy and more engagement at school.

And the positive effects are not just for English learners. Longitudinal research finds that both English learners and native speakers in two-way immersion programs score at or above grade level in both languages by middle school, and ELs perform as well as or better than peers attending mainstream English-only programs. Proponents of the dual immersion approach argue it not only results in better academic outcomes, but avoids segregating non-native English speakers and helps them stay connected to their language and culture.

"We know from the research that it does make a huge difference," said Patricia Gandara, research professor of education and co-director of the Civil Rights Project at the University of California Los Angeles. "Children who are educated in the home language … outperform the kids who have been educated in English only, and even sometimes outperform the kids who are native English speakers."

States such as Utah and North Carolina are actively promoting and funding dual-language immersion, with the former allocating more than $5 million to immersion initiatives in fiscal year 2022. But it appears the model has not yet caught on in the Twin States, where there are no dual-language immersion programs listed in the Center for Applied Linguistics' program directory.

In 2020, a Manchester school board subcommittee sought to change that, recommending that the district create specialized schools for dual-language immersion to better serve English language learners. The proposal called for two elementary-level immersion programs — one for French at Webster School and another for Spanish at Beech Street School — and a magnet middle school focused on global studies and language immersion. In high school, students would continue their language studies in college-level dual-enrollment courses.

However, there have been few updates on the recommendations since then, and plans to place EL students in more core subjects with native English speakers have been complicated by staffing concerns.

Because New Hampshire law requires English-only instruction, schools must get approval from the state board of education to implement a bilingual or dual-language program. Wendy Perron, EL consultant for the state department of education, said Education Commissioner Frank Edelblut supports the model.

"We know it's effective, we know the research supports that it is grounded in sound educational theory," Perron said. " … So I think it's only a matter of time in New Hampshire. We know our students could benefit from that."

A growing need

When Lisa Schroeder moved to Derry with her family in fall 2021, she hoped to enroll her son at a dual-language immersion elementary school like the one he'd attended in Tacoma, Washington.

Schroeder wanted him to start learning a new language at a young age, when children can easily soak up linguistic knowledge. So the dual-language option in his old district — which offered instruction partly in English and partly in Spanish for all subjects — was a perfect fit.

"When my son first started kindergarten I was actually a bit skeptical of his Spanish abilities," Schroeder said. "But by the second semester he was pronouncing words correctly and really making progress in the language."

Her search for an equivalent in the Granite State, however, turned up empty, even after expanding her scope to charter and private schools and dual-language programs in nearby Massachusetts. She ended up cobbling together a "quasi-curriculum" of online resources and YouTube videos for her son, now a fourth-grader.

"It was pretty aggravating and disheartening to learn that there weren't any viable Spanish learning opportunities for elementary children with an intermediate fluency in the entirety of New Hampshire," she said.

At the same time, the state is becoming home to more and more English learners who could benefit from this type of dual-language instruction. Even as New Hampshire's total school enrollment has declined — dropping about 13.5% between 2010 and 2020 — the population of eligible English language learners has grown.

In 2010, about 4,500 Granite State students were eligible for EL services, according to the state education department. As of 2020-21, there were more than 5,400 eligible students, the department's data show, a roughly 19% increase.

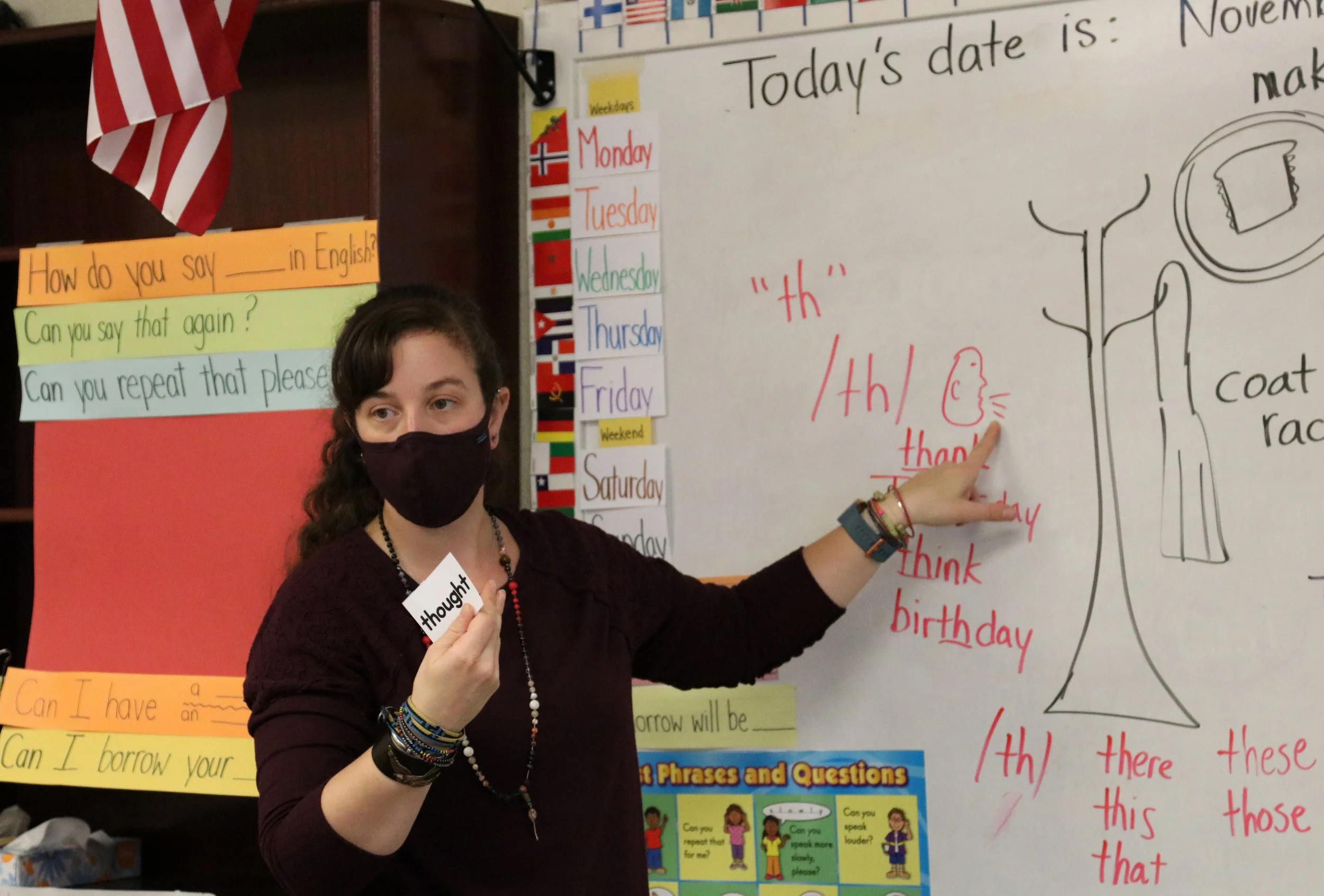

Schools identify students using home language surveys, and families can then choose to opt in or out of services. In some schools, students are pulled out of class for individual or group EL sessions, while in others, EL teachers might "push in" to the general classroom to work with students. Still others provide English immersion in a "sheltered" environment of only English learners.

Most of the state's eligible English learners — about 68% — are concentrated in Manchester, Nashua and Concord.

"Just like the students in New Hampshire, the programs are really diverse," Perron said. "So depending on the available staffing and the needs of the EL population in specific districts, the program models really vary."

Perron said the state has seen success with co-teaching models, which pair a content teacher with an EL teacher, as well as cross-certification in EL instruction for classroom teachers so they can intervene directly with EL students as needed. She also highlighted Manchester's transitional newcomer program for incoming students with little to no English.

In the Keene School District, where about 1.2% of students are eligible for EL services, instructors use the "push in" method to work with English learners in the general classroom. Instructor Jack Timmons, who works at Franklin School and Keene Middle School, said he sometimes co-teaches alongside the classroom teacher or works with a small group of English learners during language arts lessons.

Students with more significant needs or no baseline English may be pulled out for individual sessions, Timmons said. But staff try to limit out-of-classroom time, because interacting with classmates is crucial in learning the language.

"It's that peer to peer communication where the development [happens], especially the social aspect, the verbal," Timmons said. "And that's like the gateway to everything else."

EL teacher Samantha Sintros, who works at Franklin as well as the city's high school, sees the significant potential benefits of two-way immersion. But she's not sure it would work somewhere like Keene, where there may not be one dominant language among the district's relatively small group of English learners. What's more, she said the city is challenged by lack of awareness around its multilingual communities — once, after explaining her role with English learners to a native English speaking student, the student responded, "We have those here?"

"If you're in a bigger city, you hear other languages being spoken all the time, whereas the average kid walking down the street in Keene doesn't expect to hear other languages being spoken," Sintros said.

Still, with the district's population of ELs continuing to grow, Timmons said Keene's biggest need is more instructors. Families also need support navigating the school system and life in New Hampshire, and schools' ability to offer that help is often limited, sometimes shifting the burden onto the students themselves.

"I had a student today who was not at the middle school because she was translating for her mother for an insurance company," Timmons said last fall. "So the kids have responsibilities like that."

That's part of the reason the Manchester School District has added additional bilingual liaisons, who provide interpretation and guidance for EL families, to its staff. The district now employs five liaisons serving an eligible EL population of nearly 2,000 students, according to its website. District officials did not respond to requests for comment on its EL programs or the previous dual-language proposal.

Nashua EL teacher Danielle Boutin, who was named 2021 New Hampshire Teacher of the Year, knows many families have significant needs the schools can't address on their own, from lack of housing to food insecurity. She and her colleagues at Ledge Street School have partnered with community organizations to set up a clothes closet, a food pantry and a homework club, and she sees how this support can help EL families feel more connected to the school community.

Academically, Boutin would like to be able to offer more enrichment opportunities for her English learners, such as field trips, guest speakers and summer programs, as well as activities centered around their home language and heritage.

She said the goal is "finding ways to continue to highlight those cultures, those linguistic backgrounds, and helping families and students realize what a huge skill and asset it is."

Boutin hasn't heard any recent talk of exploring dual-language immersion in Nashua. But she said that's not surprising, as the district is already struggling to find enough staff for its current model. The district is also in the midst of implementing changes required under a settlement reached with the U.S. Department of Justice in May 2021 after an investigation found that Nashua failed to provide sufficient services to English learners.

Nashua administrators did not respond to requests for comment on the district's EL programs.

"In education, sometimes it feels like you only have an opportunity to do things once," Boutin said. "So you want to make sure, when you roll something to that level out, that you're doing it really, really well and you're able to support it."

Immersion in action

For Aradhana Mudambi, director of multilingual education for Framingham Public Schools in Massachusetts, dual-language immersion goes much deeper than building biliteracy skills. It's also about recognizing the identities that students bring to school with them.

"Dual-language programming is really a social justice movement to ensure the students who come in as emergent bilinguals or multilingual learners have the opportunity to learn their home language as well as English," Mudambi said.

The Bay State has about 30 two-way immersion programs offered in multiple languages, including Spanish, Portuguese and Haitian Creole. In Framingham, the model is used in three elementary schools and one middle school, and three populations comprise the enrollment: About one third of students are native English speakers, one third speak the "target" language at home and one third speak a bit of both languages.

She sees dual-language options as more beneficial than sheltered programs, which focus only on English. Sheltered models ignore knowledge that students have already built in their home language, she said, such as their letters, numbers or colors. And this gap in subject-based learning can be compounded over time.

"We're starting children from zero, regardless of what their educational path looks like. And by doing that, we're holding off the time where they can build their content in order to teach language," Mudambi said. "And therefore what we find — what the research finds — is that we never close the opportunity gap for students when they're in a sheltered English language program."

One of the biggest challenges for dual-language programs is finding adequate curriculum materials, particularly in less widely used languages such as Portuguese. Staffing is also a perpetual concern — Mudambi said it was difficult to find qualified educators even when she worked in Texas, where Spanish is widely spoken.

"I think that's exactly why a two-way language immersion program has not taken off in New Hampshire," Perron, of the state education department, said. "We have a critical shortage of EL certified teachers, and I think you'd have to find teachers who are bilingual."

Framingham offers sheltered English programs in each of its schools for students who have no English baseline or were not selected for the immersion lottery, though the dual-language immersion program enrolls some students who are not native speakers of either language. Mudambi stressed that when schools use an English-only model, they must prioritize finding ways to support students' native languages, too, such as through after school activities and take-home materials.

"That importance of keeping the language alive is so high for parents. They want their kids to have their culture, because culture and language is part of one's identity," Mudambi said. "And as a parent, you want to give that to your children."

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative as part of our Race and Equity Initiative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.