With community input, districts emphasize ‘equally important’ real-world skills to prepare students for their futures

By Kelly Burch, Granite State News Collaborative

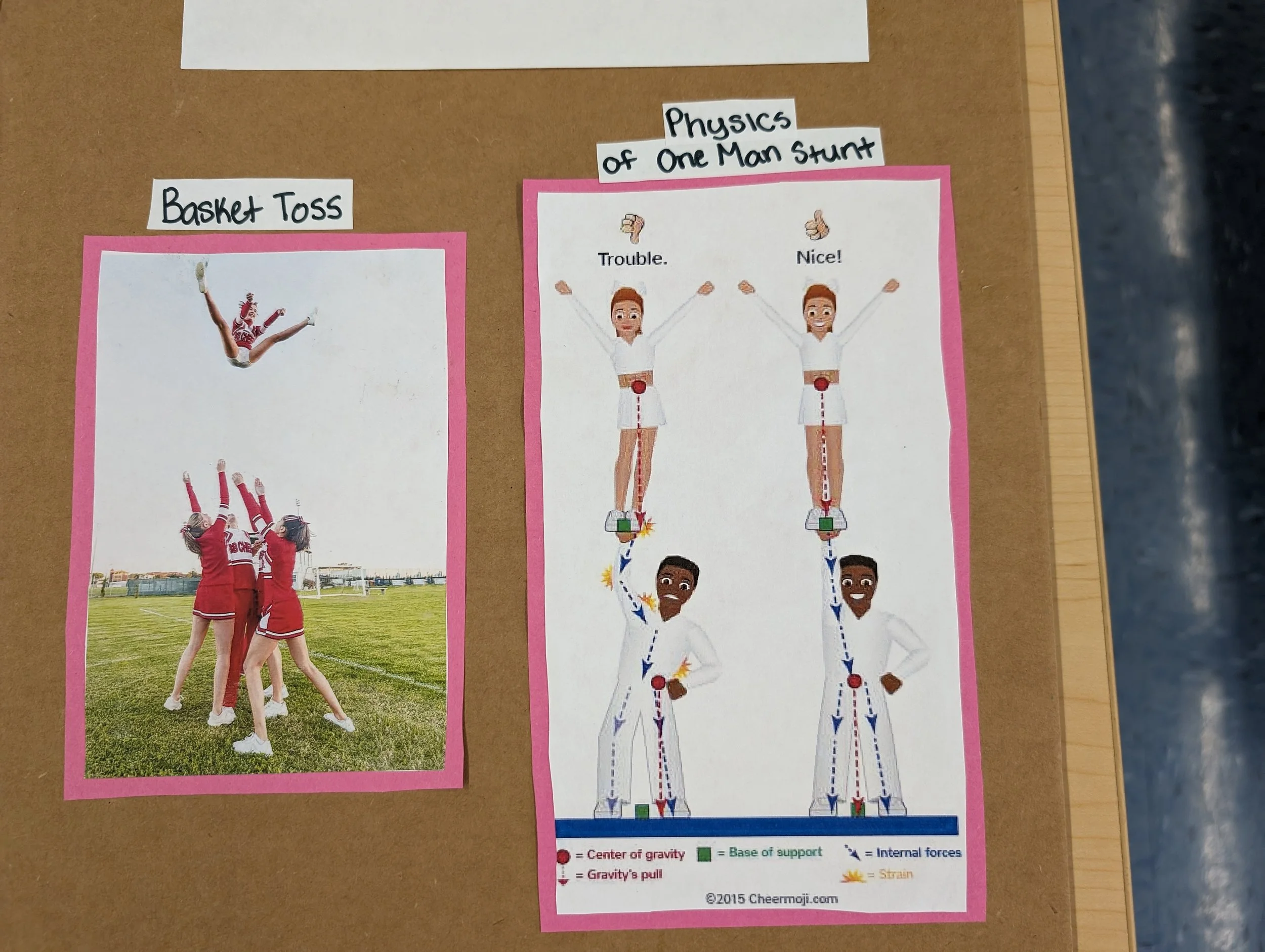

Earlier this year at Franklin High School, a group of cheerleaders got together to present their physics project. But there was no PowerPoint or test papers. Instead, the girls used cheerleading and stunting to demonstrate principles of the science.

A poster that accompanied a presentation by cheerleaders at Franklin High School, demonstrating a real-world application of physics principles. (Courtesy of Franklin High School)

Jule Finley, curriculum coordinator for the Franklin School District, said she was blown away by the confidence the students showed and the depth of their knowledge as they responded to questions from the teacher.

“It wasn’t just memorized to plop some answers on a test and forget it two days later,” Finley said. “They know that information, and they will not forget it because they’ve connected it to something they are passionate about.”

The physics presentation is just one example of a project-based, real-world approach to learning that Franklin is trying to foster, Finley said.

This year, the high school was able to be more creative and flexible with its curriculum because the district adopted a “portrait of a graduate,” a document that outlines the life skills that the community wants graduates to have, including attributes such as resourcefulness, wellness and responsibility — all of which were on display during the physics presentation, Finley said.

With the freedom to work toward those goals, teachers are thinking outside the box about how they deliver their lessons and assess students’ learning, she said, and students are more engaged than ever.

Portraits of a graduate, also called portraits of a learner, are relatively new in the Granite State but have been used around the country to define what communities want from their school systems. The portraits serve as a vision statement for school districts and are an important part of competency-based education — an approach that emphasizes real-world applications of academic skills.

The Miford School District is among at least eight around the state that have crafted their own ‘portraits of a graduate.’ (Milford School District)

The idea is catching on in New Hampshire, with at least eight districts around the state — including Conway, Hampton, Milford, Nashua and Newport — crafting their own portraits of a graduate, many with help from the New Hampshire Learning Initiative, a nonprofit dedicated to competency-based education.

These documents provide guidance for school districts to equip students with particular skills and evaluate their progress in obtaining them, educators say.

“The portrait of a graduate really is a great North Star … because everyone can answer, ‘What do you want our graduates to know and be able to do?’” said Laurie Gagnon, program director of the CompetencyWorks initiative at The Aurora Institute, a national nonprofit focused on competency-based learning.

Interest in portraits emerged in New Hampshire about three years ago, amid concerns that students didn’t have the life skills they needed to function as adults, even if they met the academic requirements for graduation, said Carolyn Eastman, director of personalized learning at the New Hampshire Learning Initiative. She has worked with six school districts on their portraits of a graduate.

Parents, teachers and employers recognized that, beyond academics, “there are a set of skills that are equally important to success after high school,” Eastman said. Portraits of a graduate allow communities to list those skills and assess them, aiming to increase students’ likelihood of success.

“We want to make sure [students are] prepared and ready for whatever future they’re going into” after graduation, said Nate Burns, principal at Nashua North High School, who is helping lead his district’s development of a portrait of a graduate.

What skills should graduates have?

Creating the portrait often starts with a basic question: What should graduates be able to do by the time they walk across the stage to accept their diplomas?

When communities ask that question — as Franklin did through community forums, meetings with local businesses, and even polls of residents at the town dump — common answers often arise, Gagnon said. Life skills come up, such as financial literacy, cooking and the ability to tap into community resources, but so do so-called dispositions, such as being resourceful, community-oriented, collaborative or resilient.

Franklin’s portrait of a graduate touches on six characteristics: a commitment to community; learning; resourcefulness; responsibility; wellness; and humanity, which the document defines as “recogniz[ing] the impacts others have on me and my impact on others.”

The Henniker School District has crafted a portrait with three tenets: envisioning a graduate who is a “respectful collaborator, effective communicator, and knowledgeable problem solver and creator.”

All of this may sound abstract, but when they work well, portraits allow school districts to structure their educational approach to facilitate these skills, Gagnon said.

“It’s important it doesn’t just stay as a poster on a wall,” she said. “You’ve got to say, ‘What are we doing to help our learners become what we’re envisioning for them?’ That can drive lots of changes in the system.”

That’s what’s happened in Franklin, according to Franklin High Principal David Levesque.

“This year, we’re embedding it into everything we do,” he said.

The Franklin School District crafted its ‘portrait of a graduate’ after a series of community forums, meetings with local businesses, and even polls taken at the town dump. (Franklin School District)

The result has been more interdisciplinary learning, such as field trips into the community and an increase in extended learning opportunities — internship-like programs that allow students to explore different career paths.

One government class attended city council meetings and formed a mock council to better understand how local government works. In another class, students prepared a YouTube video to teach others about mindfulness, building their communication skills, their understanding of wellness and their grasp of technology. In a class that paired physics with sports, the cheerleaders were just one example of hands-on presentations.

“That’s the direction we’re trying to get to, where we’re not just using a paper or a trifold” poster to assess learning, Levesque said.

In response, he said, the school has seen improvements in students' attendance and engagement. “The portrait of a graduate thing has saved us this year,” he said.

An approach for the entire school system

In Nashua, the team working on the document has opted to call it a portrait of a learner, rather than a graduate, because if the ideas aren’t implemented until high school, “it’s kind of too late,” Burns said.

Instead, he wants the Nashua portrait to be used from preschool all the way until graduation. Eventually, the document will provide not only guidance, but a framework for assessing students and measuring their growth in non-academic skills in much the same way their academic progress is monitored.

“Prior to this … we didn’t have a way to report out on it, and we definitely weren’t speaking the same language” about non-academic skills, Burns said.

Nashua’s document is still being drafted, but Burns says it emphasizes critical thinking, grit and relationship-building.

Nashua is “not spending a ton” on the process, but creating a portrait of a graduate can be expensive. Franklin has spent $650,000 on the effort since 2019, which includes site visits to other schools around the country and students' experiences in the community. The funding was provided through grants from the Barr Foundation, a Boston-based nonprofit focused on education reform, among other initiatives. The same foundation provides grant funding that the New Hampshire Learning Initiative uses to support districts in creating their portraits.

Other states have a statewide portrait of a learner. The New Hampshire Learning Initiative has crafted a portrait of a New Hampshire learner that includes five skills: critical thinking and problem-solving; communication; collaboration; adaptability; and learner’s mindset. However, the portrait isn’t part of state graduation requirements or the state’s minimum standards for public school approval, known as the 306s.

Because of New Hampshire’s emphasis on local control, “the majority of the work is happening at the local level,” said Eastman. “While we have a statewide portrait, we know that local supersedes states.”

With that in mind, Eastman expects to see more communities creating a portrait of a learner.

“Life skills have become very important to the kids, the parents and to the community,” she said.

These articles are being shared by partners in the Granite State News Collaborative. For more information, visit collaborativenh.org.