In addressing a complex phenomenon, growing consensus sees a powerful indirect link

By Johnny Bassett and Ryan Lessard, Granite State News Collaborative

Click the link to watch the full interview on NH PBS's The State We're In.

Editor’s note: This article is another installment of “Invisible Walls,” an ongoing joint project of the Granite State News Collaborative, NH Business Review, Business NH Magazine and NH Public Radio that describes how exclusionary zoning laws have reinforced areas of persistent poverty, impacting many aspects of community life, including crime, public health, affordable housing and access to economic opportunity in Manchester. The team used Manchester as a case study, but the same sorts of exclusionary zoning practices present in Manchester are common across the state, and likely have had similarly broad effects.

Wanda Castillo Diaz Photo, Courtesy

Wanda Castillo Diaz is not afraid to walk around center city Manchester.

“I am aware of my surroundings when I walk around,” she said. “But there are others who are really afraid.”

Castillo Diaz has been working in Manchester neighborhoods as a community health worker for 21 years. She’s also a member of The Center City Neighborhood Group, a group of residents and other stakeholders from center city who have been meeting every month for the past six years to build community engagement and improve the neighborhood.

The group formed after a daytime shooting near a local restaurant left them feeling as though they needed to do more. [See Sidebar]

Residents know outsiders describe their neighborhood as a magnet for poverty and crime and are frustrated with how hard it has been to shake that reputation.

“The residents feel stigmatized,” she said.

The persistence of center city’s crime issues is easy to spot in the last decade of crime data from the Manchester Police Department (MPD). According to the collaborative’s analysis of calls for police service between 2006 and 2020, the number of crimes reported per resident was significantly higher in center city than anywhere else in Manchester (see map). Compared to the suburbs in northwestern and northeastern Manchester, parts of center city reported roughly five times as many calls for service.

Crime is a notoriously complex phenomenon, and no single theory can explain all crime, but interviews with criminologists and an analysis of the city’s crime data suggests some of this disparity is the indirect result of the city’s historical zoning policies. Since the 1920s, zoning laws in Manchester have helped reinforce pockets of concentrated poverty and, indirectly, higher crime. Crime control is not the primary goal of land use zoning, but there is a growing consensus among researchers and city officials across the country that zoning has a powerful indirect effect.

As Manchester makes its once-in-a-decade revision to the zoning laws, a closer look at the relationship between zoning and crime may help planners better achieve the goals outlined in the Master Plan, which was approved last year. It may also help them dramatically improve the quality of life for some of the city’s most vulnerable residents, who have long been burdened with a disproportionate share of the city’s crime, providing a helpful example for other New Hampshire cities dealing with similar issues.

Todd Bookman/NHPR

Lt. Matthew Barter walks the neighborhood near Union and Auburn Streets, just east of the SNHU Arena.

Crime rates and poverty

''Are criminals born or made?” The ongoing debate around this question highlights the difficulty of knowing what to do about crime in Manchester. Each answer suggests a different solution.

For scholars in the “born” camp, such as neuroscientist Adrian Raine of the University of Pennsylvania, criminality is caused by one’s biology. Therefore, according to Raine’s 2013 book The Anatomy of Violence, the best ways to reduce crime at scale are to prevent it from happening through strong public health programs for children, when their brains are most malleable. More controversially, Raine also advocates the use of long-term detention to limit the potential damage done by adults whose “broken brains” could not be helped.

The opposing argument from the “made” camp, however, argues that the causes of criminality originate outside the body. Writers in this camp, such as Jane Jacobs and Robert J. Sampson, have argued that the choice to commit a crime is heavily influenced by one’s surroundings, especially the prevalence of poverty, violence, or structural decay, as illustrated by the famous theory that fixing broken windows is an effective method of reducing crime.

Put another way, this second group of writers thinks that crime can be reduced through clever city planning.

If Lt. Matthew Barter of the MPD walked the halls of academia rather than the streets of Manchester, he would likely fall into the second camp. He has been thinking for years about the city’s crime issues, and he has become convinced local conditions play a major role.

Barter had long wondered about the causes of crime, like many of his colleagues, but he started thinking about it more intently in the mid-2010s, when the department began using a computer program that sifted through historical crime data to make guesses about when and where crimes would occur. That initiative, spearheaded by Barter, was a major step for MPD into the field of predictive policing, a strategy of data-driven police work widely celebrated in the early 2010s but later criticized for reproducing bias in its algorithms. (Police departments now are often coy about whether they use predictive policing, but it is likely still being used across the country.)

Barter said Manchester’s software consistently predicted above-average levels of crime in a handful of neighborhoods, including parts of the West Side and in center city.

“These are the lousiest socioeconomic parts of the city,” Barter notes.

That is no secret to Manchester residents, said John Rivera, pastor of the non-denominational Christian church Hope Tabernacle on Cedar Street in Manchester.

Rivera said many residents of center city feel safe walking the sidewalks and want to see their neighbors thrive, but even with this abundance of goodwill, some residents are struggling to get by.

“They’re in survival mode,” Rivera said.

Rivera has seen some center city residents struggle to make their rent payments, even for low-cost and run-down apartments. Adding to the burden, many of these same residents struggle with stress and mental illness, or in some cases drug addiction, which adds additional financial pressures and increases the likelihood of crime.

According to Joseph Lascaze, a longtime Manchester resident and now an organizer with the ACLU of New Hampshire, this correlation shouldn’t be a surprise.

“You’re packing people into these areas, the only areas that these guys are going to be able to afford,” Lascaze said. “That’s what happens.”

This connection is also easy to spot in data from MPD and the U.S. Census Bureau. At the level of the census tract, areas with the highest number of calls for service per capita are also home to some of the city’s deepest poverty (see map).

Experts say this pattern is common across the country.

PHOTO BY ALLEGRA BOVERMAN

“At the macro level, we pretty much know at this point that the main cause of crime is concentrated poverty,” said Tate Twinam, a professor of economics at The College of William & Mary.

“If you have a lot of people living in low-opportunity neighborhoods, with high unemployment, high poverty rates, and so on, that's where you're going to see most of the crime.”

This is such a common trend in large communities it’s tempting to think it explains the behavior of individuals as well, but this isn’t supported by the evidence, said John MacDonald, a professor of criminology at the University of Pennsylvania.

“These theories don’t suggest 100 percent that there's going to be higher crime. It depends on other factors, too. Even in the highest-poverty, highest-density neighborhood, still the majority of people are not going to be committing crime or be victims of serious crime,” MacDonald said.

“It's not like the built environment predetermines what everyone living in a place is going to experience. People make decisions.”

The trouble for many people living in high-crime areas, however, is they cannot move to another neighborhood. They are walled in by high prices in the rental and housing markets, among other obstacles. This is where the role of land use zoning comes in.

Todd Bookman/NHPR News

Pastor Rivera says his community reflects the neighborhood: multicultural and multigenerational.

Crime and zoning

According to veteran investigator and Manchester Police Reserve Officer Bob Freitas, police in Manchester have long understood that crime is tied to geography.

Freitas said between 1985 and 2009, when he was working as a city police officer, Manchester cops often referred to one part of center city as the “combat zone,” an allusion to the seedy reputation of an adult entertainment district in Boston that was created by city zoning in 1974.

The area known to MPD officers by that name in Manchester – bounded by Merrimack, Auburn, Chestnut, and Beech Streets – encompasses parts of the downtown and Kalivas/Union neighborhoods, according to the City’s neighborhood map, and parts of tracts 14 and 15 in Census Bureau records.

“From our perspective on it, we knew where the problems were, and they didn’t venture out past that,” said Freitas. “It seems to me, just driving through the city, those spots haven’t changed.”

Previous reporting by the collaborative has explored the link between zoning and poverty in Manchester, finding the city’s zoning policies have helped segregate the city by income.

That reporting focused on the housing market, but as criminologists and city planners are increasingly aware, exclusionary zoning policies have surprisingly broad effects.

“What often I think gets missed in this work,” MacDonald said, “is how important the actual zoning of residential land use is for crime.”

“When you have a place where there's economic deprivation, or there might even be a case where people get stuck in a neighborhood for generations living in poverty, these things together create a social environment that makes crime more likely,” he added.

“Zoning feeds into that by helping to essentially create those concentrated pockets of poverty,” Twinam said.

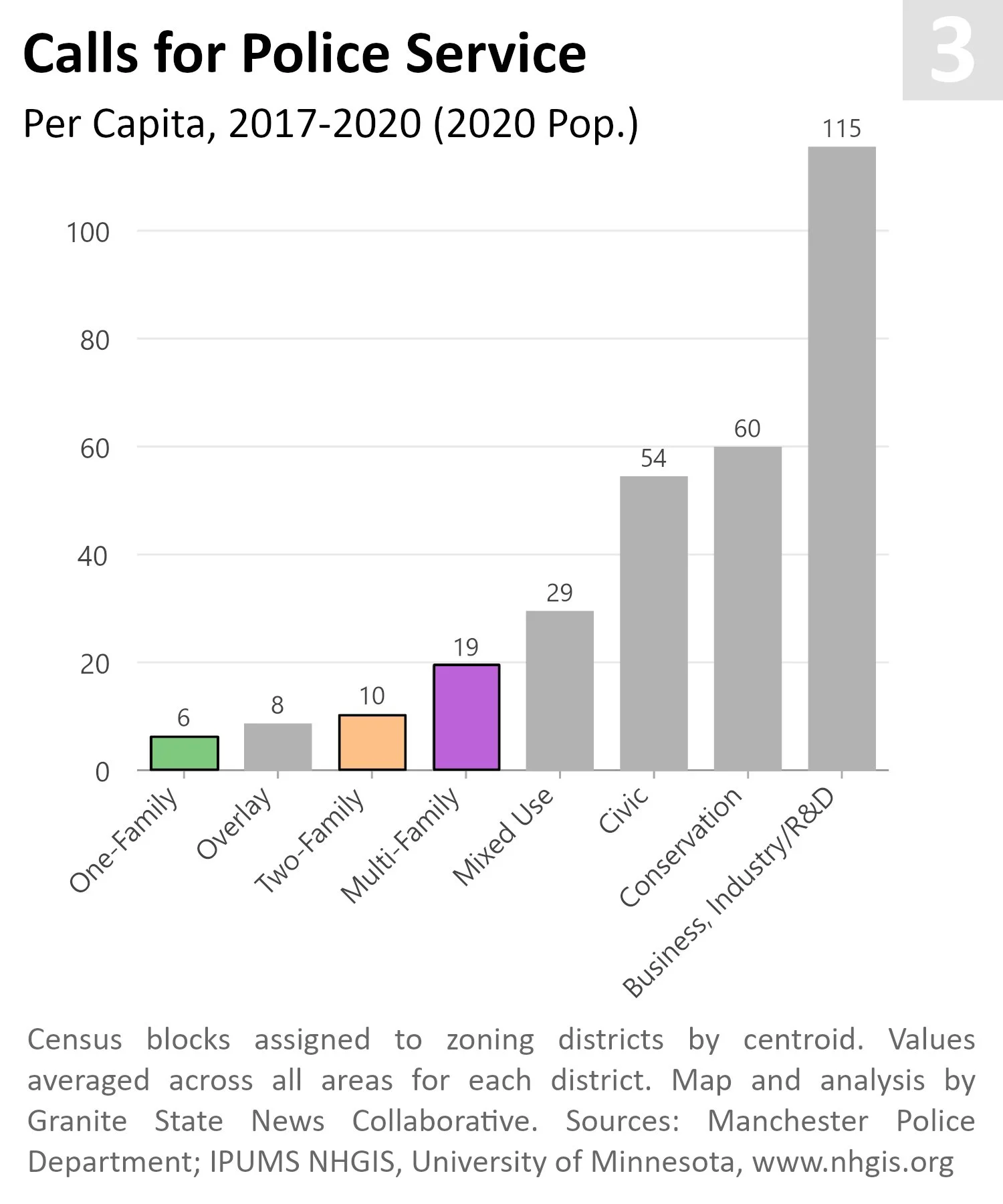

The correlation between zoning boundaries and crime is easy to spot in Manchester. Among residential neighborhoods, the areas zoned for multi-family in recent years have also experienced higher rates of reported crimes per resident, as measured by calls for service.

Between 2017 and 2020, since the last change to the zoning map was recorded in the current zoning ordinance, multifamily areas experienced more than three times more reported crimes per capita than areas zoned exclusively for single family (see chart).

Twinam and MacDonald also noted how zoning affects crime not just through the residential housing market, but through the commercial market as well.

“Commercial areas tend to have higher crime because we have a higher ambient population. That’s a finding we see city after city, decade after decade,” MacDonald said.

PHOTO BY ALLEGRA BOVERMAN

In Manchester, areas zoned for commercial uses experienced by far the greatest number of calls for service of any zoning type in the city.

Echoing patterns seen across the country, Manchester’s use of exclusionary zoning means that the spillover effect from high crime at commercial properties has had a disproportionate effect on high-density housing.

According to the collaborative’s analysis of data from the Manchester Assessor’s office, less than 20 percent of single-family homes are within 100 yards of a commercial property, compared to more than 80 percent of multi-family, many of which are in center city.

City officials have expressed their intent to use zoning to help reduce crime, though they have not provided details about what form those efforts might take. In a section of the current Master Plan, the authors wrote that neighborhood design should be done with crime reduction in mind, citing a widely-used framework called Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (CPTED).

According to the International CPTED Association, an advocacy group, these principles can be applied in a wide range of programs, including mixed-use zoning districts, neighborhood watches, improvements to night time street lighting, and broad-based community groups and events.

When asked on multiple occasions earlier this week whether and how CPTED principles would be incorporated into the forthcoming zoning revisions, the city planning team declined to comment, citing a busy schedule.

PHOTO BY ALLEGRA BOVERMAN

Zoning reforms and ‘Problem-solving’ cops

The good news is that even if poverty and crime are currently high in a given area, experts say those trends can be reversed.

“One example is there have been studies looking at the demolition of these big public housing projects in places like Chicago and other cities that were big hotbeds of drugs and crime,” said Twinam, who was not involved in either study.

“These big housing projects get demolished, and the people who live there end up getting spread out to different neighborhoods, some to public housing, some to private housing that is subsidized. And what you see is they don't really take the crime with them. Overall crime in the city just falls. And it's just people basically responding to their environment.”

Studies like these have not only emboldened scholars like MacDonald and Twinam, but also those from Notre Dame, Georgetown, and the University of Denver to call for the use of land use law to help reduce crime.

Like CPTED, these methods typically use city planning to make areas more friendly to public use, which also tends to make them less friendly to criminals. These reforms can take many forms, but they often include allowing for more mixed-use zoning, which both encourages public use at all hours of the day and encourages the development of mixed-income neighborhoods.

“When we have mixed-use and mixed income, you find that the crime rates [are] lower [overall],” MacDonald said. “It’s not going to be as low as affluent single-family only, but it's substantially lower than when you have single-use [separated from] high-density residential. This suggests if you have a greater distribution of income in a place, there's benefits for everyone living there.”

To their credit, city officials have already suggested some of these specific reforms.

“Housing units should be distributed throughout mixed-income, walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods,” the authors wrote in the Master Plan. They also recommended that the city “eliminate or reduce” zoning districts that are exclusively single-family.

Even if the city does implement some of these changes, however, it will take years for newly allowed development to impact the city’s housing market.

For Rivera, the pastor of Hope Tabernacle, he sees more property ownership as a solution. During his time as a pastor in New York City he said one of the few things he experienced that actually affected change was an investment in residential homes.

“We saw the community change when the city and the state … subsidized home ownership,” Rivera said. “I saw a block transform because there were owners now.”

Other tools are at the city and community’s disposal.

As MacDonald emphasized, the police still have an important role to play by doing what they can to help reshape the physical environment.

PHOTO BY ALLEGRA BOVERMAN

MacDonald described a strategy of policing that was first proposed in the 1970s in which police are encouraged to think creatively about each crime issue they encounter and the potential strategies they could use to deal with it – beyond just using their arrest powers.

MacDonald described a study run by University of Pennsylvania criminologist Anthony Braga in which Braga studied how police in Lowell, Mass., implemented this strategy, which is called problem-oriented policing.

“They randomly assigned officers to basically put more officers in a place, but it wasn't just flooding an area with more police. The police were supposed to engage in these problem-solving tactics.”

Over time, MacDonald said, crime went down. “The police were doing things like getting abandoned cars removed, or if there's a bunch of trash built up, if there's a place with no street lights, you know? Now, the police aren't doing the work themselves, but they can identify what to do through their own observations, and then trying to get other city agencies and organizations to respond to the problems in the community.”

“Obviously, the police can't change the zoning. But they can at least help,” he said.

For its part, the Center City Neighborhood Group regularly plans initiatives to try to improve the streets and build social investment and cohesion in a place unfairly mired in isolation and sometimes fear.

They focus instead on cleaning trash off the streets and alleys, petitioning for better street lighting, organizing flower plantings to beautify a curb or murals to cover up graffiti. The group organizes annual cleanups and, through its affiliation with NeighborWorks Southern NH, covers half the cost to spruce up badly vandalized buildings with murals, with the other half covered by landlords.

“People really do care,” said Rivera. “They just don’t always know what to do to fix the problem.”

– Melanie Plenda contributed to this report

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative as part of our race and equity project. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.