Some districts found that computer-literacy provided another barrier to reaching families in the ELL programs.

Editor's Note: This story is part of a series that takes a look at how school districts across the state responded to the challenges of remote learning and plans for improvements in the fall

By Kelly Burch

Granite State News Collaborative

This summer, Claudia Castaño wanted to give her English language learner (ELL) students a leg up for the fall — no matter what the 2020-2021 school year should look like. The best way to do that, she decided, was to focus on teaching them technology, getting them comfortable with services like Google classroom and document sharing in an effort to eliminate one of the barriers to success that her students had when Nashua switched to remote learning in March.

“Our mission is to help these kids to explore the technology during the summer. I hope they can apply the skills if they go to remote learning,” said Castaño, who is the ELL Community Outreach Coordinator for Nashua North and Nashua South High Schools, and the coordinator of the summer school program for ELL middle and high school students in the district.

Castaño has 179 students enrolled in the program, more than the 120 she has in a typical year. That’s surprising, in a year when many other districts found that summer school enrollment was down. Most of the students — 143 — are participating remotely, while the students without internet access or devices at home come to the Boys and Girls Club in Nashua, where they complete the tasks under the direction of Castaño and the three other educators who work in the program. Although attendance was down in Nashua during remote learning, most students are showing up for summer school.

“[The teachers] feel so happy,” Castaño said. “In the spring a lot of kids were absent, but right now the attendance is stable.”

English language learners (ELL) — children whose first language isn’t English or whose families primarily speak another language — make up just over 3% of the students in the state, according to 2019-20 estimates used to determine state aid to localities for the cost of providing an adequate education. However, that varies widely from district to district: Manchester has the highest population of ELL students, while some towns have no ELL population. ELL students, sometimes called ESL or ESOL students, attend mainstream classes and complete assignments, but also get additional support from ELL teachers.

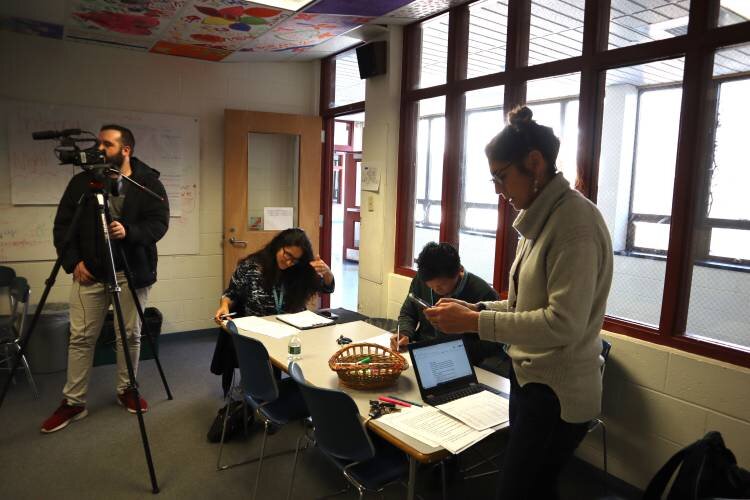

English language learners (ELL) — children whose first language isn’t English or whose families primarily speak another language — make up just over 3% of the students in the state, according to 2019-20 estimates used to determine state aid to localities for the cost of providing an adequate education. However, that varies widely from district to district: Manchester has the highest population of ELL students, while some towns have no ELL population. ELL students, sometimes called ESL or ESOL students, attend mainstream classes and complete assignments, but also get additional support from ELL teachers. Pictured here is Concord High School English-Language Learners Social Worker Anna-Marie DiPasquale preparing for a ConcordTV recording of Mandarin and Portuguese translators reading information about COVID-19 that was streamed online for families of students who don’t speak English. (LEAH WILLINGHAM / Concord Monitor)

During remote learning access to and understanding of technology was a major barrier to education for ELL students and their families. In some cases technology makes it easier to overcome a language barrier — many ELL instructors use services like WhatsApp, Talking Points and Gmail to translate text and email notices to parents, for example. However, ELL families are often in lower socio-economic positions, with limited access to devices and the internet. That can make remote learning especially difficult for ELL students.

“They don’t have experience with the technology, with Google classroom. The parents don’t have computers,” Castaño said. “There was a lot of frustration.”

While she’s helping her students understand technology better this summer, she’s also hoping that the district will do more translation and interpretation if the need for remote or hybrid learning comes up this year.

“They need to find a better way to communicate with the families if it’s remote learning,” Castaño said. “We have interpreters, but in this situation we need more.”

In A High ESL District, A Focus On Keeping In Touch

In Manchester, 16% of the students are ELL, which means that Nicole Ponti, executive director of English learner instruction and equity for the district, has about 2,000 students to keep track of. In addition, there are more students who have tested out of the ELL program, but whose parents speak little English and require some interpretation and support from the program.

When the switch to remote learning happened, Ponti focused on making sure that all parents and families understood what was happening, the expectation for their child, and the option for completing work. To do that, the district used teachers, community liaisons and volunteers to relay information in the more than 50 languages spoken in the district.

In order to streamline the effort, Ponti and her staff appointed a contact person for each family. The district hired interpreters to translate essential information, which was posted in written and audio format in the languages most common in the district. Informal phone trees sprung up to make sure that everyone had the latest update.

As the dust settled, Manchester established a formal monitoring program. Each day, ELL teachers would report on any families that needed to be contacted. If a student wasn’t in touch with a teacher for two days, someone from the district reached out.

“Everything happened so quickly, we didn’t want to lose anyone,” Ponti said. “A protocol was in place to make sure no one was left behind and to make sure everyone had everything they needed” including food and medical care. At one point, Ponti and a principal delivered a computer to a student’s home.

“It was a feel of, ‘We’re going to help you no matter what,’” she said.

In New Hampshire, each district funds its ELL program as part of the school budget. Federal funding is available under Title III, based on the number of ELL students, or incidence level, that a district has. While high-incidence districts like Manchester have more funding, they often have a higher case load of students per ELL teacher and coordinating services can be trickier, said Wendy Perron, English Language Education Consultant for the New Hampshire Department of Education. However, those districts also benefit from having a rich community in place, including community liaisons and volunteer interpreters.

“Low [incidence] districts don’t have that suite of resources,” Perron said.

In A Low-Incidence District, More Time For Personal Connection

Normally Jean Fahey, program coordinator for the ESOL (English to Speakers of Other Languages) Department in SAU 6, spends a lot of time in her car. In the district, which covers Claremont and Unity, only about 1% of the student population are ELL, but they’re spread through five different schools.

When the district switched to remote learning, Fahey could simply call her students, giving her a lot more wiggle room in the day.

“I definitely spent more time during COVID meeting with my students,” she said.

This year Fahey, the only ESOL teacher in SAU 6, has just nine students. During remote learning she was able to check in on them daily and collaborate more closely with their classroom teachers. Through Google Classroom she could see what assignments the students were and weren’t completing, and work through the difficult ones alongside her students. She even arranged socially-distanced, outdoor one-on-one lessons with a few of her students.

The accountability of having Fahey check in each day helped her students succeed during remote learning. “They all passed,” she said. “They all did very well.”

Still, the students missed out on the social connection for school — which is also very important for learning English, Fahey said. Many of her students don’t have many friends because they’re new to the community, so they weren’t likely to arrange a visit or even contact friends by phone or social media.

“They definitely missed their peers,” she said. One student in particular — a high schooler who was new to the country in 2019 — felt isolated without in-person learning.

“When you don’t know the language you don’t call people up and say, ‘hey how are you doing?’” Fahey said. “That face-to-face communication definitely benefits my students and they missed that. They did well academically, but the social piece is huge, and for my students it’s that much more important.”

Building Relationships To Support Future Remote Learning

In SAU 56, which covers Somersworth and Rollinsford, ELL students make up roughly 4% of the district. Teaching got easier with time for Jolene Francoeur, ESOL Teacher at Idlehurst Elementary School.

“Every week I had another win,” Francoeur said.

Initially, reaching parents and helping them choose between digital instruction or paper packets was tricky — it took some time to reach a few families. But once contact was established, Francoeur used translation apps to help communicate with parents regularly. Although the district didn’t have the time or resources to translate instruction for work packets (New Hampshire law mandates that ELL students complete their work in English, with necessary support), Francoeur was able to put a Google translate link on all parent pages for Google Classroom.

She became more confident when she learned what was working not just for the other ELL teachers in the district, but in other districts around the state. Perron, at the Department of Education, organized weekly calls for ELL teachers throughout the state where they could share tips for remote learning. This was especially beneficial in districts that had a low number of ELL learners, known as low-incidence districts.

During remote learning access to and understanding of technology was a major barrier to education for ELL students and their families. In some cases technology makes it easier to overcome a language barrier — many ELL instructors use services like WhatsApp, Talking Points and Gmail to translate text and email notices to parents, for example. Pictured here is Sara Neema, a 2016 graduate of Concord High School and ELL tutor, who calls numbers on a list of more than 50 New American families to update them on the district’s response to COVID-19. Neema speaks English and two African languages, including Swahili. (Credit The Concord Monitor)

“In high-incidence districts, teachers were working to share tips and experiences,” Perron said. “The low-incidence districts were struggling. They just needed more support from colleagues.”

In addition to the calls, ELL teachers around the state also started sharing translated documents and resources, which was helpful especially for smaller districts like SAU 56, Francoeur said.

“Our objective in the beginning, when we were first going remote, was just to keep them at level, to keep them where they’re at,” she said. With time, she realized she could still teach new material. “Once we got much more comfortable with remote learning, we were able to figure out ways to move the content forward.”

ELL students screen into the program and are tested yearly using the ACCESS Test, which measures proficiency in listening, speaking, reading and writing. Once students score a 4.5 out of 5 on the test, they’re no longer eligible for ELL service. Most districts finished the ACCESS test in March before the switch to remote learning. The test does offer an online option, but it must be administered in a school building. The state has a plan in place to do preliminary screenings for new ELL students remotely, if necessary, Perron said.

Having had the summer to plan for remote or hybrid learning should make distance learning easier on teachers, students and parents if it’s required, said the ELL teachers who spoke with the Collaborative.

Ponti, of Manchester, would like to see districts streamline what remote service and apps they’re using so that families are not overwhelmed. That, in addition to having clear and consistent expectations for work, would help ELL families know where to turn.

“Using a limited number of resources, rather than a whole plethora of those resources, would simplify it in a way that’s most easy, rather than creating another barrier,” she said.

Two professional development days that Ponti ran for classroom teachers about working with ELL students were filled beyond capacity. She was heartened to see that even with all the stress and uncertainty about next year, teachers are prioritizing serving their ELL students and working with ELL instructors to plan effective remote learning.

“Collaboration and co-planning is going to be post important for the child’s success — that we’re all on the same page instructing that child,” she said. “We all have the same goal, all know the students’ strengths, and are trying to get them to the next level together.”

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.