At least five local programs will receive money from settlements with opioid manufacturers and distributors.

Kelly Burch

Contributing Writer

Each week, employees of The Keene Serenity Center provide about 80 rides to people who are in recovery from substance-use disorder through its transportation program.

Recently, these journeys have included taking someone to Boston for eye surgery, delivering groceries to a person who has health challenges, and helping someone who hasn’t held down a job for ten years get to work each day, said Sam Lake, executive director of the Keene Serenity Center.

To stay in recovery requires a lot of support and “the transportation program is really a master for that,” he said.

Demand for the Serenity Center’s transportation program has been growing over the past few years, and it’s currently at maximum capacity. Lake would like to expand the program, but said the nonprofit has “a big hole for funding for that.”

Now, a $20,000 grant from Cheshire County will buoy the program. The money is part of opioid settlement funds being distributed throughout New Hampshire after state, county and local governments sued opioid manufacturers, whose prescription and marketing tactics contributed to widespread opioid-use disorder in the state. New Hampshire has been one of the states hit hardest by the opioid epidemic, with 416 opioid-related deaths in both 2020 and 2021.

85 percent of the settlement funds go to the New Hampshire Opioid Abatement Trust Fund, a fund established in 2020 for the purpose of distributing the settlement money throughout the state. Money from the fund is distributed through grants. The first round of grant funding has been awarded, but not yet publicly announced, said state Sen. Cindy Rosenwald (D-Nashua), chair of the Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission, which oversees the trust fund.

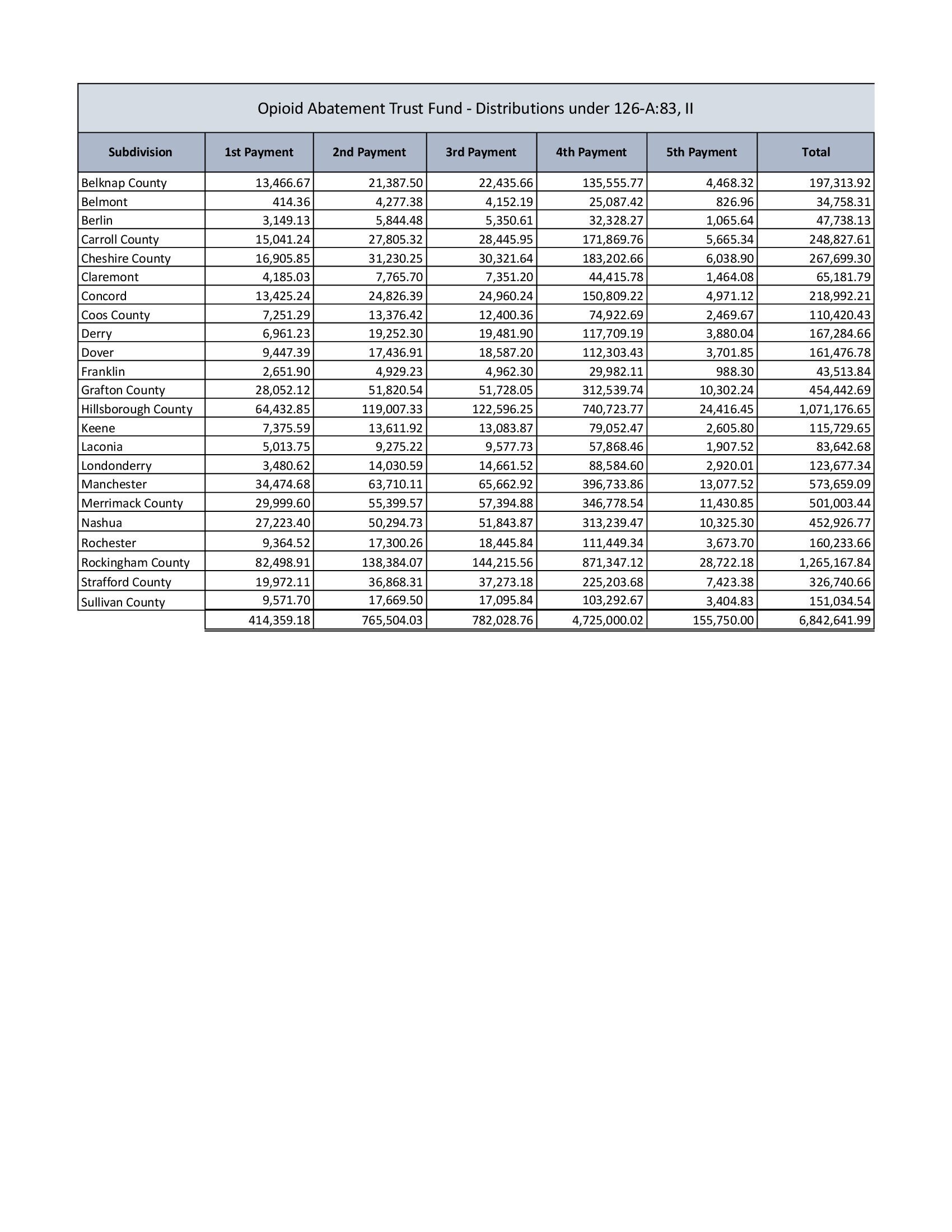

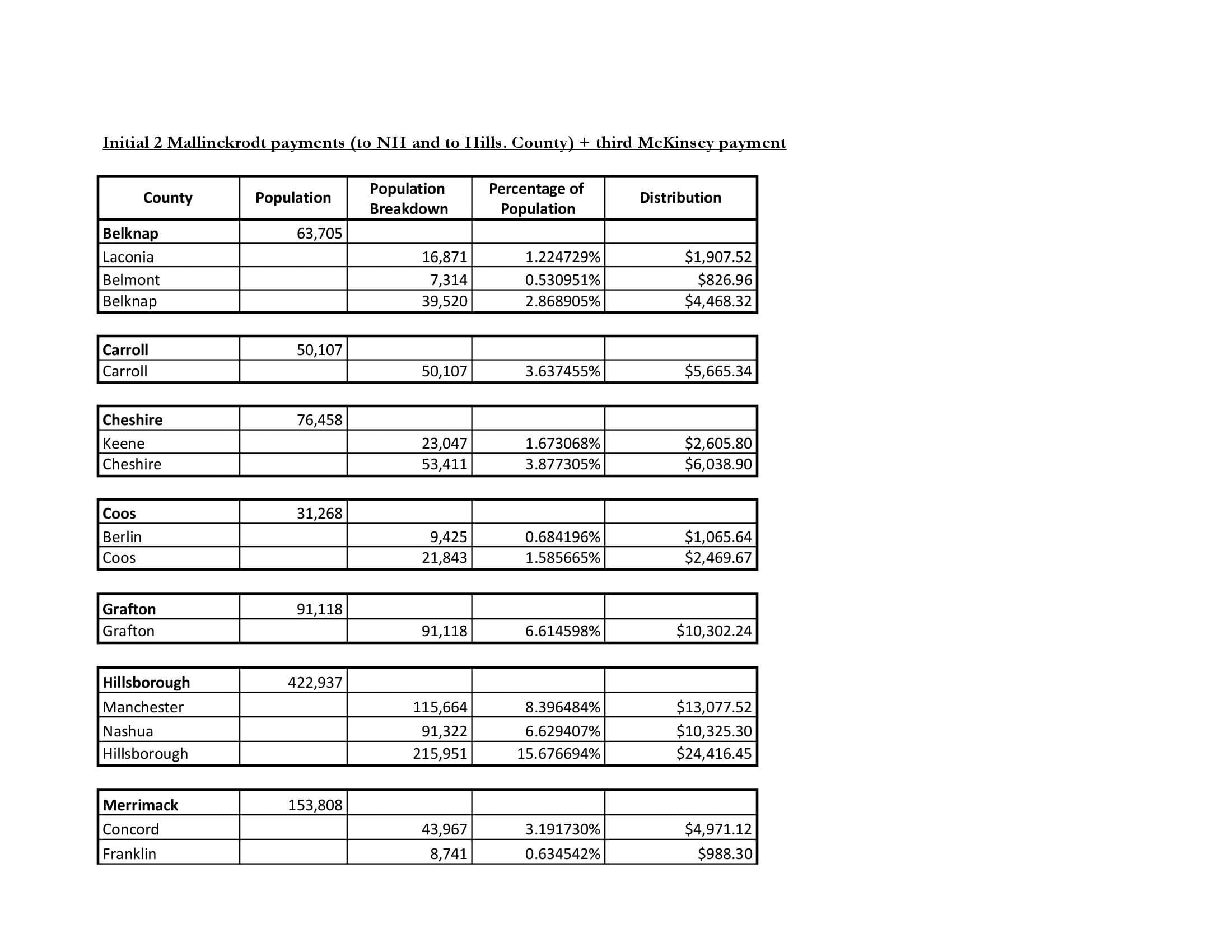

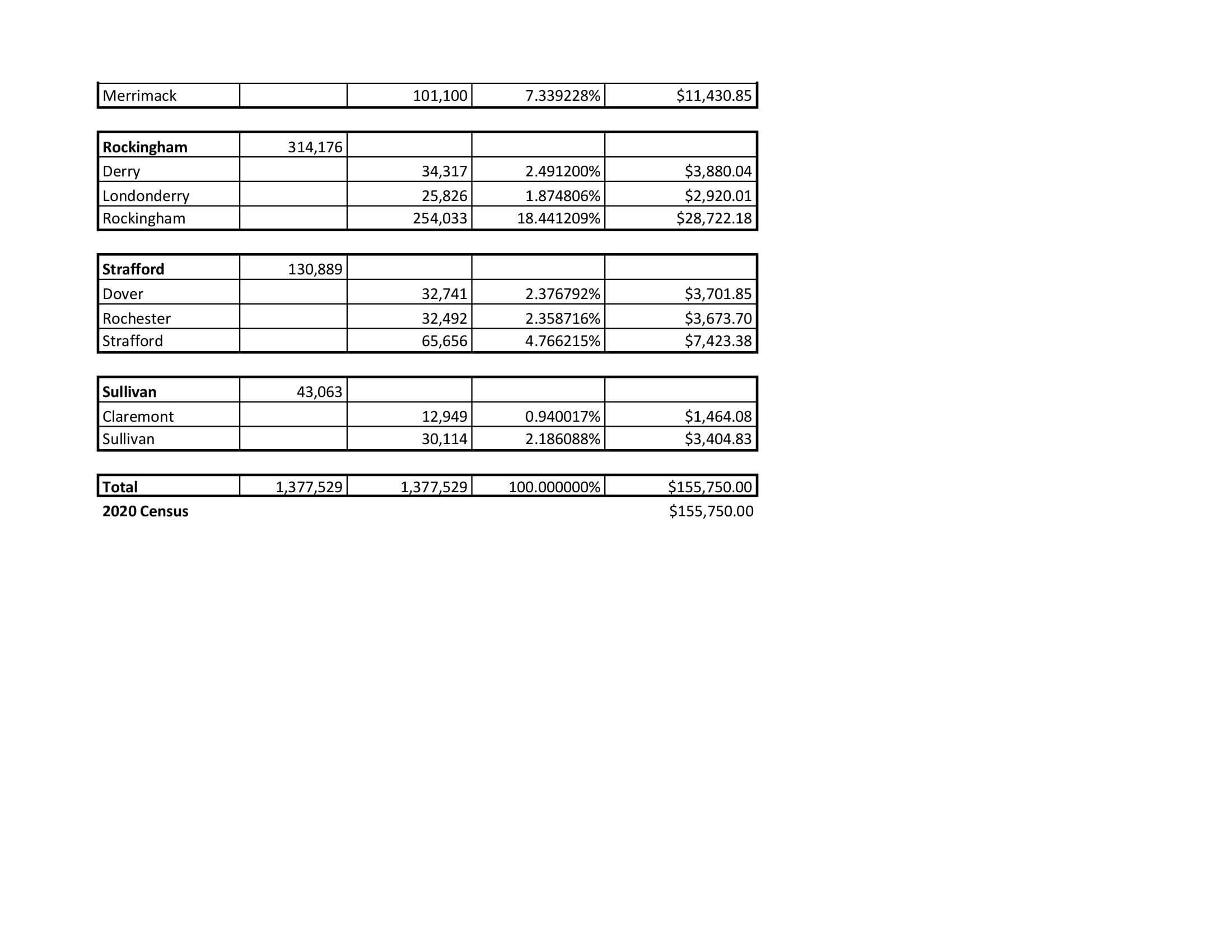

The other 15 percent of the funding goes directly to the 23 cities and counties, including the City of Keene and Cheshire County that also joined the lawsuits. The money is awarded to each litigant based on its population.

To date, New Hampshire has received $46 million in settlement funds, according to N.H. Deputy Attorney General James Boffetti. Many settlements, including bankruptcy settlements of opioid manufacturers, are still pending, but Boffetti anticipates that the state will receive roughly $310 million over the next 18 years. So far, Cheshire County has received $267,699 in settlement funding, while the City of Keene has received $115,729.

Although officials say the settlement amounts pale in comparison to the impact of the opioid crisis New Hampshire has faced, they provide much-needed money to address the decadeslong crisis. In the Monadnock Region, the impact of funds may be “subtle,” according to Cheshire County Administrator Christopher Coates.

“At the end of the day, I think that over time, you’re going to see we have a better-run system,” Coates said. “This added revenue is allowing us to be much more proactive than we would be without the funding in place.”

Cheshire County is giving five grants

Cheshire County will distribute five $20,000 grants to help address opioid use in the county, according to Coates. Three of the grants will go to county-run programs through the: Cheshire County Department of Corrections, Cheshire County Treatment Court and the Cheshire County Sheriff’s Office. The remaining two will go to The Serenity Center and Reality Check, a Jaffrey-based nonprofit providing recovery and prevention services.

Sheriff Eli Rivera said he plans to use these funds to train the county’s law enforcement.

While there are existing trainings for law enforcement responding to opioid-related emergencies ranging from overdoses to people facing withdrawal, Rivera said the trainings often don’t address the unique challenges rural law enforcement is met with, such as the fact that officers usually work individually, rather than in a team.

In addition, many small police departments cannot afford to send officers to top-notch trainings that require travel. Rivera said he plans to bring nationally-recognized trainers to the county in order to alleviate this problem, and make education more accessible to local departments. He’s still working out the precise details of the trainings, he noted.

At Cheshire County Treatment Court, the $20,000 grant will be used for incentives and transportation for participants, according to Program Coordinator Alison Welsh. The court serves Cheshire County residents with diagnosed substance-use disorder, who are facing felony legal charges related to their addiction. Participants plead guilty but are not sentenced to jail. They are instead required to follow an individualized treatment program created by the drug court. Gift cards, rental assistance and dental care are much-needed incentives that don’t have other sources of funding, Welsh added.

“They encourage positive behavior working towards their (participant’s) recovery goals, such as completing levels of treatment and periods of sobriety,” Welsh said in an email.

For the Cheshire County Department of Corrections (DOC), grant funds will support a Medications for Opioid-Use Disorder (MOUD) program at the county jail. This protocol, also called medication-assisted treatment, is clinically proven to help people get into and maintain recovery. The jail started the program in 2017 and today, about half of inmates participate in the program, said Douglas Iosue, superintendent of Cheshire county’s DOC. As of April 4, 49 of 102 inmates were on medication-assisted treatment, Iosue said.

MOUD comes at a massive cost

In 2022 alone, the cost of the medications rose by about $10,000 because more inmates were on MOUD. Additionally, the administration of the program cost the jail an extra $124,186 in staffing expenses annually in 2021 and 2022, according to Iosue. The jail is considering hiring additional staff to run the program, he added.

Because of this large cost of medication-assisted treatment, the jail is applying for more grants, Iosue said. Along with other county departments of corrections, the Cheshire County DOC is preparing a grant application directly to the opioid abatement fund, independent of the $20,000 of county funding.

The Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission voted in March to approve a round of grants to help reimburse the cost of medication-assisted treatment, according to Sen. Rosenwald. However, the specifics of the grants, including how much the DOC will be able to apply for, are not yet finalized.

“That will help us to fairly reimburse our costs not just of medication itself, but our additional staffing time and travel time,” Iosue said.

While the jail won’t be introducing any new programs with the funding, Iosue said the money will allow the DOC to “catch up” on the cost it’s bearing because of the ongoing opioid epidemic.

“The impact and cost has been increasing gradually, and I think the fund will be helpful to properly reimburse and help provide service and treatment relating to it,” Iosue said.

Two nonprofits “hanging on by a thread” look forward to county funding

While Coates said that county funding will always be prioritized for internal county programs, the funding is also being used to support local nonprofits.

“There are nonprofits that are hanging on by a thread,” Coates said. “We want to do what we can to get the money out as quickly as possible.”

The county is also intentionally keeping administration costs of these grants low. Tracking deliverables and accounting for every bit of money spent can typically eat up to a third of a grant, according to Lake of the Serenity Center. But, the county is only asking for a simple update of how the money was spent, allowing for more of the dollars to be targeted toward the programs they’re meant to support.

At Reality Check, Founder and CEO Mary Drew said funding will be used to bolster the recovery coach program. These are professionals that meet with people in jail or in the community to help support and guide them through the challenges of early sobriety.

In addition, Reality Check will use some of the funding to provide employer education to help businesses retain and assist people with active opioid-use disorder or who are in recovery. That initiative was particularly appealing to the county, Coates said, because of its widespread impact on the local economy.

“That intrigued us,” Coates said. “They work with businesses that have individuals that are employed but are struggling with addiction, to keep them employed and work them through this moment in time.”

Zero-tolerance policies around substance-use disorder are ineffective, Drew said. Policies like allowing people to attend recovery meetings during their workday can help retain employees, ultimately providing much-needed support for people with opioid use disorder and lowering hiring or training costs for employers.

City of Keene seeks to hire a social worker for the police department

As a litigant on the lawsuits, the City of Keene receives a portion of settlement funds directly. Like the DOC, the city also plans to apply for additional grant funding from the opioid abatement trust, said City Manager Elizabeth Dragon.

“The thought is to be able to combine with the state program, to create a much bigger impact, versus spending it when we get the smaller amounts,” Dragon said.

Last weekend, Dragon announced that Keene would like to use funding to add a social worker to the city’s police department. The social worker could follow up after calls that involve opioid-related emergencies to connect people with resources and treatment.

"That’s really needed,” she said. “There’s a huge opportunity for integrating those services into the police department for the future.”

Yet planning a new position is difficult, given the uncertainty of the total settlement amounts and the one-time nature of grants from the abatement fund, Dragon said. Even if Keene doesn’t receive state funding, Dragon said she plans to add a social worker position to the city’s budget for fiscal year 2025.

Dragon’s concerns about the availability and predictability of the funding are shared.

“It’s one time funding,” said Drew, of Reality Check. “When we’re talking about one time funding, it is inadequate in the sense that we’re trying to sustain what we’re building, and it’s difficult to sustain services without sustained funding.”

For immediate assistance, Cheshire County residents can visit The Doorway, a referral hub at 24 Railroad St. in Keene. The Doorway is open Monday through Friday, 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Support through the state’s 24/7 hotline is available at 211.