Money will come into the state over the next 18 years.

By Kelly Burch, Granite State News Collaborative

After thousands of overdose deaths and millions of dollars in economic disruptions due to the opioid abuse crisis, New Hampshire is on track to receive roughly $310 million to address some consequences of the crisis.

“These cases are geared toward stopping the next person from dying and to make sure there is help available to them,” said Deputy Attorney General James Boffetti. “It’s meant to help the living, keep them alive and stop this crisis.”

The money is coming from various settlements with opioid manufacturers, distributors and retailers including CVS, Walgreens and Walmart that contributed to the widespread use of highly addictive opioid medications in the state, Boffetti said. To date, New Hampshire has received $46 million; the $310 million is not yet guaranteed, but is the amount that Boffetti projects the state will get, given pending settlements. Some settlements feature lump-sum payments, while many are spread over 18 years, Boffetti said.

Now that the settlements are beginning to come in, the state has a precise formula for how the money will be disbursed — and Boffetti has hopes that the impact will be felt throughout New Hampshire.

“Are [the settlements] adequate? No. There’s no amount of money that could fix the damage that they did. It’s enormous damage to [our] communities,” he said. “There’s no amount of money that’s going to make people feel like we fixed the problem. Will it make a difference? You bet.”

Most of the settlement funds will be put into the New Hampshire Opioid Abatement Fund

The majority of settlement money that comes into the state – 85 percent, or about $263.5 million – will be deposited into the New Hampshire Opioid Abatement Trust Fund.

The fund, which was created by state legislation in 2020, is overseen by an advisory commission and falls under the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS).

Money in the trust fund will be distributed as grants, said state Sen. Cindy Rosenwald (D-Nashua), chair of the Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission. There are 16 categories of projects that can access the money, according to state law. They are outlined in RSA 126-A:83-86 and include reimbursement for the costs of emergency services related to opioid use disorder (OUD); detox, housing and transportation costs for people with OUD; training for addiction- and mental-health counselors, and more.

“It’s basically prevention, treatment and recovery broadly,” Rosenwald said.

Any organization, from municipalities to schools or nonprofits, can apply for grants related to the purposes outlined in legislation. Rosenwald has lodged a bill, SB32, that would require the fund to disperse at least $5 million annually for as long as there is that much money in the fund.

When the commission considered the first round of grant applications last fall, the demand far exceeded the $6.6 million available. The commission received nearly 50 applications for projects, totaling $24 million, Rosenwald said, and was only able to award 17 grants.

While recipients have been notified, the grants have not yet been made public. Rosenwald expects them to be publicly available after the state Executive Council votes to approve the project contracts in May.

During the commission’s March meeting, it voted to move forward with a new round of $5 million in grant applications to reimburse the cost of medication-assisted treatment, Rosenwald said. She expects all of 10 counties in the state will apply.

In Cheshire County, the Department of Corrections (DOC) is preparing, with other county DOCs, to apply for that grant funding, said Douglas Iosue, superintendent of the Cheshire DOC. As of April 4, 49 of 102 inmates in the county jail were on medication to treat opioid use disorder. The jail not only needs to provide the medication, but also the staff hours to carefully supervise inmates as the medication is administered. One medication, Suboxone, needs to dissolve under the tongue for 15 minutes, Iosue said. Since there’s a risk for abusing the medications, corrections officers need to watch inmates the whole time.

“It’s not like you pop it in your mouth, swallow water, and you’re done,” Iosue said. Over the course of a day, administering medication-assisted treatment adds hours of work, he said. In 2021 and 2022, the jail spent $248,372 to cover the increased staffing needed to administer medication-assisted treatment.

“That whole process is not what correctional officers spent their time doing five years ago,” Iosue said.

Fifteen percent of settlement funds will be directed toward cities and counties

The remaining 15 percent of settlement funds will be divided among 23 government organizations that signed on to opioid lawsuits. These include all 10 counties in New Hampshire, and 13 cities and towns.

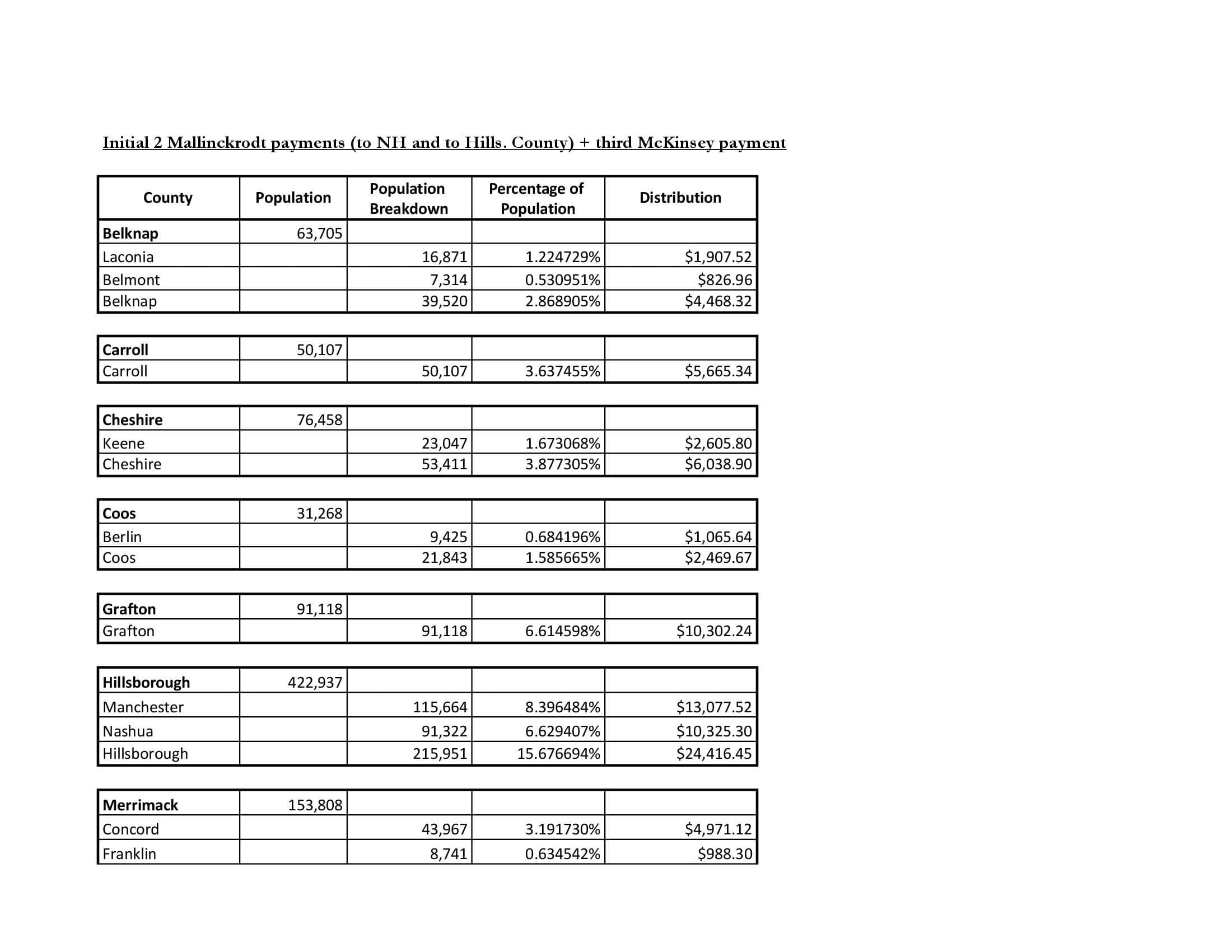

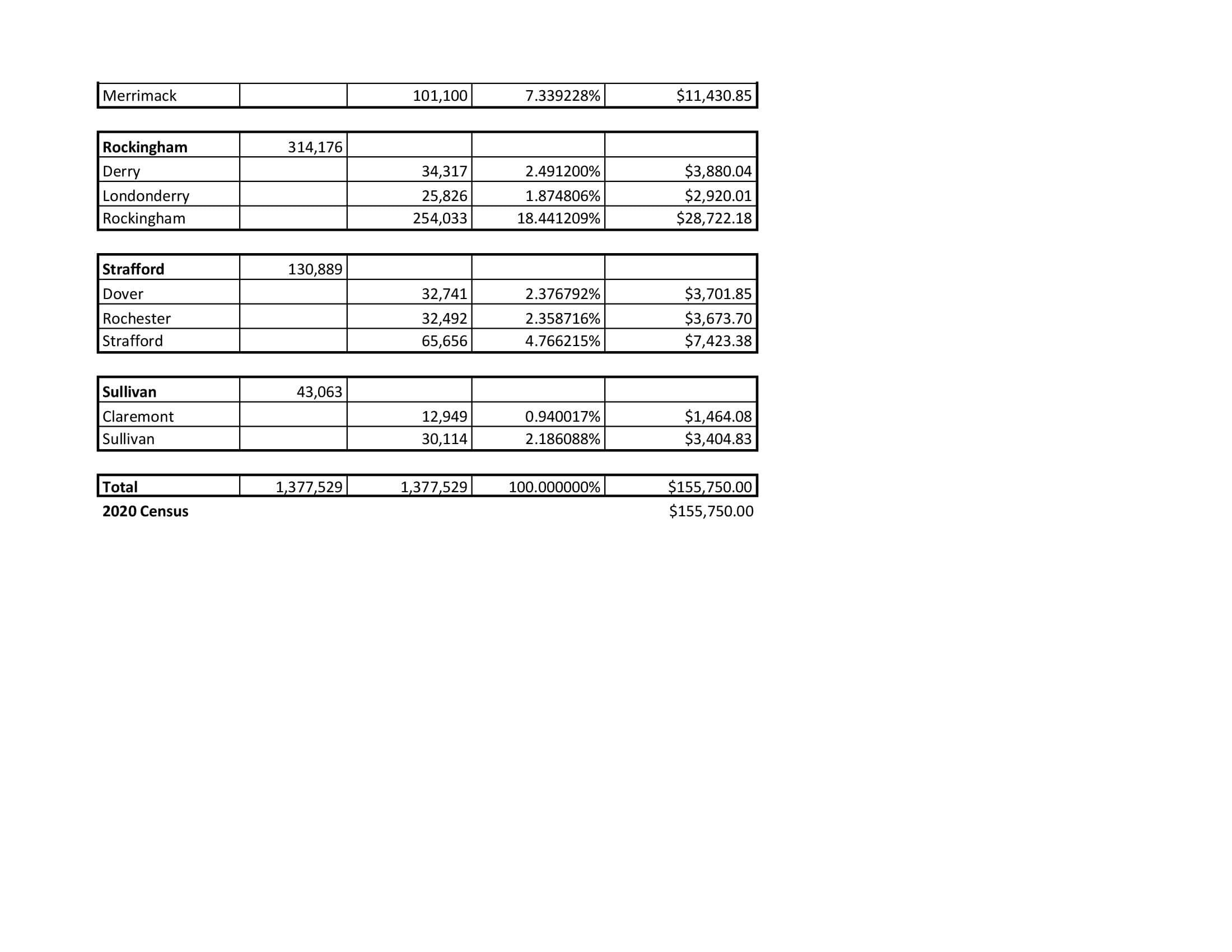

Those funds are distributed as they come in, based on the population of a county or city, Boffetti said. For counties, money is awarded based on their population, minus the population of any cities or towns that are also litigants. For example, Hillsborough County receives money based on its population, minus the populations of Nashua and Manchester, which are both litigants and will receive their proportion of funding directly, Boffetti explained.

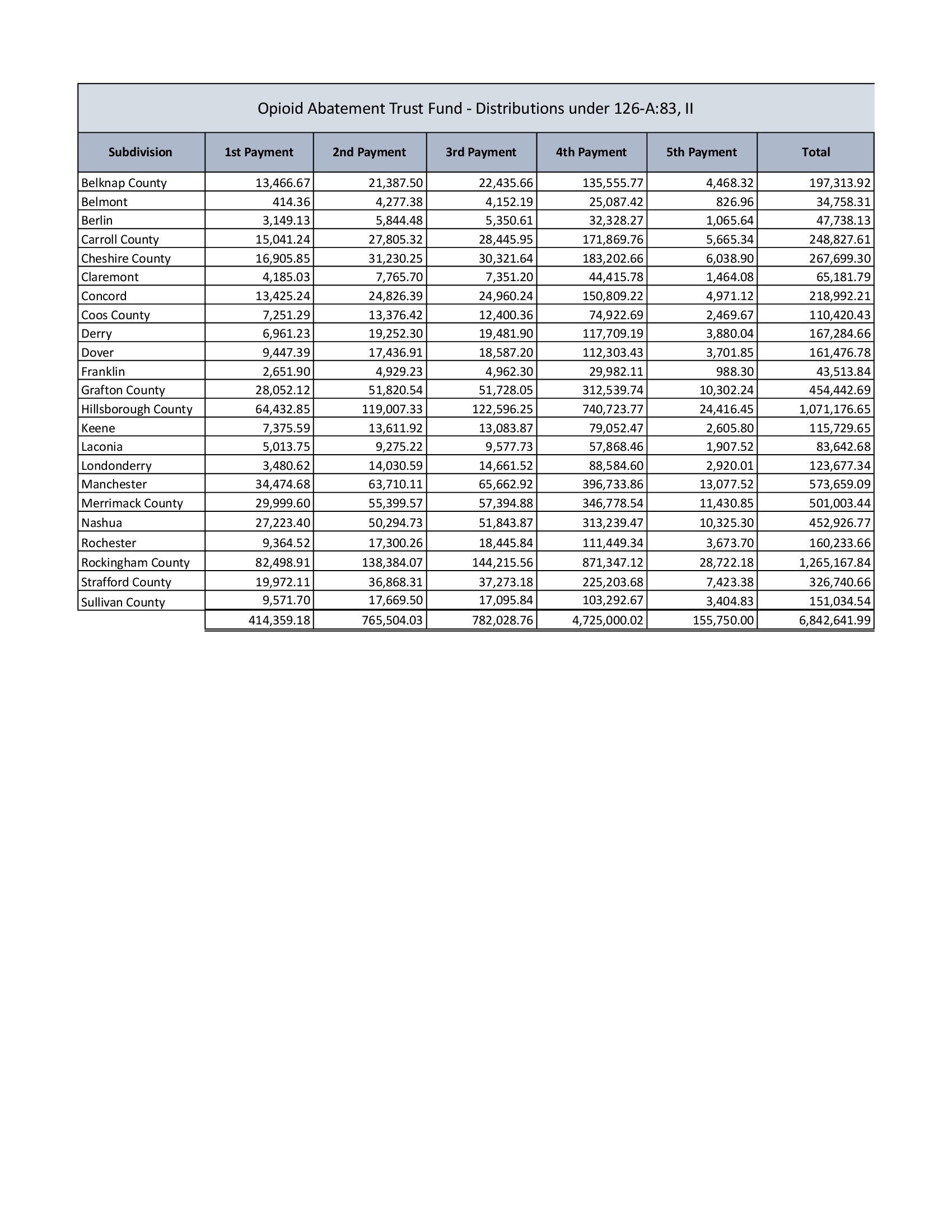

Eighty-five percent of opioid settlement funds go to the New Hampshire Opioid Abatement Trust and will be distributed as grants statewide. The other 15 percent of opioid settlement money is divided between 23 counties, cities and towns that signed on to the lawsuits, based on their populations as reported in the 2020 census. Here’s a list of those entities, and the portion of the 15% that they will receive, according to information from the Attorney General’s Office:

Belknap County: 2.87%

City of Laconia: 1.22%

Town of Belmont: 0.53%

Carroll County: 3.63%

Cheshire County: 3.87%

City of Keene: 1.67%

Coos County: 1.58%

City of Berlin: 0.68%

Grafton County: 6.61%

Hillsborough County: 15.67%

City of Manchester: 8.39%

City of Nashua: 6.63%

Merrimack County: 7.33%

City of Concord: 3.19%

City of Franklin: 0.63%

Rockingham County: 18.44%

Town of Derry: 2.49%

Town of Londonderry: 1.87%

Strafford County: 4.76%

City of Dover: 2.38%

City of Rochester: 2.36%

Sullivan County: 2.19%

City of Claremont: 0.94%

So far, five payments totaling $6.8 million have been distributed to counties and cities, according to information Boffetti provided. Rockingham County has received the most, with over $1.2 million in funding. The town of Belmont has received the least, at just under $35,000.

The funds sent to the litigants need to be spent according to the settlement agreements that they came from, Boffetti said, but it’s largely up to the litigants to decide how to appropriate the money. For example, in Grafton County the money is being used to support medication-assisted treatment at the Department of Corrections, according to paperwork submitted to DHHS. As of November, Manchester was holding on to its money pending proposals for use, according to a similar report. Cheshire County recently announced five $20,000 opioid-settlement grants.

Building a healthier future, but with limited funding

The opioid epidemic has touched nearly every aspect of life in the Granite State, said Kathryn Kindopp, a member of the advisory commission and administrator of Maplewood Nursing Home in Westmoreland.

“You hear about opioids and you don’t stop to think how it can impact your personal life, your professional life, almost every service you can imagine. The whole community,” she said. “It’s so impactful.”

At Maplewood, for example, rules around dispersing pain medications have changed dramatically, requiring additional staff hours. That challenge has been even greater in other organizations, like departments of corrections, Kindopp said.

“If you think about added administrative burdens because of this, everything has grown exponentially,” she said.

That’s the basis of the lawsuits, which are essentially public nuisance cases, Boffetti said.

“By flooding New Hampshire communities with opioids, way more than was medically necessary, they created a public nuisance in the state,” he said.

None of the funds paid out are in the form of damages — money paid because of past consequences of the crisis. Instead, they’re intended to mitigate the future impact of what Boffetti calls a “glut” of highly addictive opioids.

"Abatement is geared toward correcting that and fixing the [situation] that they created,” he said.

But despite the massive amount of money coming into the state, and the long duration of payments, building lasting solutions is challenging, said Iosue, superintendent of the Cheshire County Department of Corrections.

“One of the risks is that ultimately that fund won’t be around forever,” he said, echoing a common concern from people who spoke with the Collaborative. “We can’t build infrastructure… on temporary funding.”

Mary Drew, CEO of Reality Check, a Jaffrey nonprofit that provides substance use and recovery services, says it’s time New Hampshire dedicated more money toward addressing substance misuse.

Other states “have built pretty intense infrastructure that funds prevention, treatment and recovery services on a grand scale, built into the budget,” she said. “New Hampshire has a significant problem. It has a problem significant enough to well-inform a dedicated line item in the budget.”

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.