By Angela Matthews, for Black Heritage Trail NH

Although born in the West Indies, Benjamin Darling’s ancestry traces to the Sengal-Gambia region of Africa. Much of his story is unclear, and legend surrounds his name. It is said that he rescued the man he was enslaved to when their boat was shipwrecked, and, for his loyalty, was awarded his freedom. Another story contends Darling escaped slavery. How he came to the Phippsburg area of Maine is not known. However, he was known there as “sturdy, industrious” and “with many staunch friends.”

On July 6, 1794, for 15 pounds, Ben bought Horse Island (so called because horses used to harvest ice from an inland pond were kept there during the summer). It is now known as Harbor Island. Darling moved to the uninhabited island near Phippsburg with his White wife, Sarah Proverbs, and their two sons, Benjamin and Isaac. They lived out their days on the island with their children and grandchildren. Benjamin, Jr., and his wife, Priscilla Emmons, had five children. Isaac and his wife, Patience Wallace, had nine children.

MALAGA ISLAND, MAINE

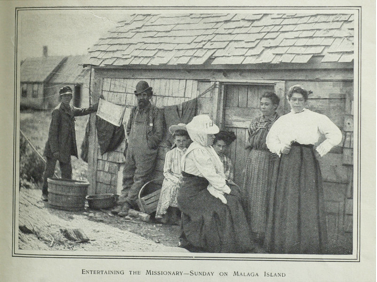

Horse Island (See DAY #2) remained under the Darling family ownership until Isaac Darling sold it to Joseph Perry in 1847. It was common practice in that day for Native Americans and fishermen of various ethnicities to leave their gear and lobster traps on the islands that dotted Casco Bay and to build temporary and even permanent shelters where they lived as squatters. They were not consistently counted in census, most often did not pay taxes, and seldom voted. Thus it seemed natural for Isaac, Ben Jr., and their families to row from their homes on Horse Island to nearby Malaga Island, where they established residence alongside other mariners and fishing families.

By the late 19th century, the coast of Maine and its many islands began attracting the attention of a wealthy class seeking vacation properties. Suddenly these islands became very desirable, while their humble inhabitants simultaneously became undesirable.

Around that time, several widely read, sensationalized sociology studies suggested — and the burgeoning eugenics movement supported — the notion that “removing decaying stock would improve the moral fiber of society.” Over several years, a public case for eviction of all the families of Malaga was carefully constructed in ongoing news reports and journal articles; it moved ahead with the full support of Gov. Frederick Plaisted.

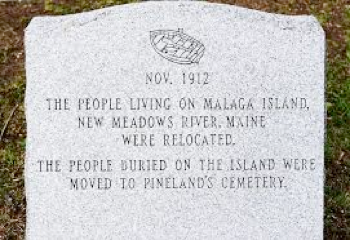

By 1913, all 45 Malaga residents were removed and their homes burned to the ground. Some were compensated for their properties and moved to mainland towns like Phippsburg and Meadowbrook. Others were less fortunate and were sent to the Maine School for the Feeble Minded, built in 1908, in West Pownal. It became the only relocation option for eight of Malaga’s residents, five of whom died within months of their incarceration. To be consigned to the home took only a doctor’s signature, but getting released from it took years. The bones from the Malaga cemetery also were dug up and reinterred near the site of the school on Pineland Farms.

A newspaper account in January 1913, Cleaning up Malaga Island – No Longer a Reproach to the Good Name of the State, stated, “Not only have the inhabitants of the island been raised to a standard of living they probably never dreamed of before and all done for them that is possible under the conditions, but the state had saved a nice little bundle of coin as well.” The island was sold to an individual who had political connections.

In 2010, almost 100 years later, the Maine state legislature passed a resolution expressing “profound regret” for what it did to the residents of Malaga Island. Later that year, on a September Sunday, Gov. Baldacci went to Malaga to personally express the state’s apologies. In the crowd that day was Marilyn (Darling) Voter of South Portland, the great-great-great-great-granddaughter of Benjamin Darling. “I feel like I’m on hallowed ground,” she said. “When I first stepped on [the island], I thought I was going to fall down and cry.”

The island today is a public preserve, maintained by the Maine Coast Heritage Trust.

This article is part of an ongoing series aimed at highlighting and honoring the stories of notable Black historical figures and families who helped shape New Hampshire and Maine. These stories were originally collected by the Black Heritage Trail of New Hampshire for a project with the Episcopal Church of New Hampshire. Stories are being shared with the partners in The Granite State News Collaborative."