Race and Equity Project

The Granite State News Collaborative is embarking on a new, multi-year reporting project examining race and equity in New Hampshire. We will be telling a story that is long overdue: how the diverse communities that make up New Hampshire are vital to the economic and cultural health of our state.

Community engagement

In order to do this project justice we will enlist input from our communities of color. We pledge to listen deeply, report rigorously and make solutions central to our mission. To participate in the project in any capacity, contact GSNC Director, Melanie Plenda at melanie.plenda@collaborativenh.org

Some ways you can participate include joining our community edit team, participating in community listening sessions, giving us feedback and suggesting story ideas, suggesting resources that would help us better understand our communities, applying to become a freelance reporter with the Collaborative, or sharing your own ideas of how you would like to participate.

You can also engage with us through our social media accounts on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

Partnership

The members of the Collaborative will join together to tell a multitude of important stories as part of this project. We will highlight the stories of people of color in New Hampshire and work with them to amplify their voices. We will investigate the policies and systems in place that have had disproportionately negative impacts on communities of color. We will analyze available data that can show us where disparities exist, and we will rigorously report the impact of those disparities on our communities.

And we’ll do it all with an eye toward solutions that may help address the inequities that exist.

Our areas of focus include:

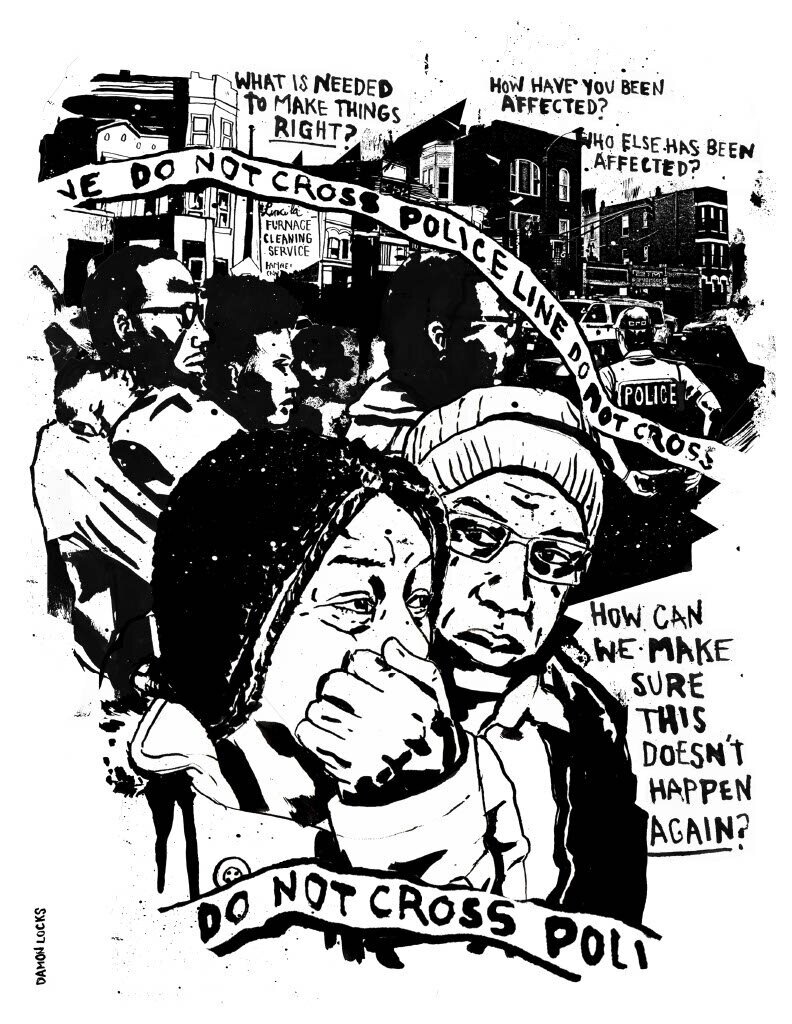

Policing/criminal justice

Economic opportunity

Affordable housing

Health

Education

Access to civic engagement

Environmental Justice

Arts, Culture and Science

Related Projects

Read and share our race and equity stories

As a teenager growing up in Portsmouth, Valerie Cunningham was proud of her family’s African American heritage, but she was also curious about local Black history. While working at Portsmouth Public Library, she discovered Brewster’s Rambles About Portsmouth. From Brewster’s stories about local Blacks, Valerie found clues to a history that until then had been invisible. She began a quest that would consume the rest of her life as researcher, historian and chronicler of Black Portsmouth from 1645 to present day.

“I’ve heard the word ‘diversity’ quite a few times,” began United States Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, “and I don’t have a clue what it means. It seems to mean everything for everyone.” That is how the Justice responded to an opening statement made last fall by legal counsel defending affirmative action in college and university admissions. Seemingly casting doubt on the underlying premise of race-conscious policies – i.e., that a diverse student population performs better academically – Thomas’ incredulousness runs counter to a robust consensus around the meaning of diversity and the value it has in education and society more broadly. I confirmed this consensus through my work producing a literature review looking into the meaning and value of diversity in public education.

Timothy Blanchard, born in Wilton, New Hampshire, in 1791, the eighth of ten children, was not yet 21 when his father, George Blanchard, turned over to him management of his veterinary practice and land holdings.

Although his father was still alive at the time of the 1820 federal census, “Timo Blanchard” was listed as head of the household of six, including a number of “free people other than Indians.” Blanchard property had for many years served as a place of refuge for a small rural community of free African Americans.

William Haskell, a noted basket maker, was born to John and Lovee Haskell in 1819 in Warner, NH. The Haskell family lived on Couchtown Road and John probably labored on local farms or seasonally as a mill hand.

Inez Glenn Bishop was born in Florida in 1927. But it wasn’t until she moved North that she realized her skin color made her feel like a second-class citizen.

She and her husband, Frank Bishop, moved to Manchester, NH, in 1947, following her mother, Bertha Evans, and her brother-in-law. The Bishops found not many people were willing to rent to Blacks. And then there was work.

Prince Hastings is recorded as living in Warner by the 1820 census. His small home was high in the Mink Hills next to a small wetland now known as “Chocolate Swamp.” Prince probably worked as a laborer for local farms. It is not known what brought him to Warner or where he came from but the 1820 census indicates several other African-American families in Warner (Clark, Haskell, Cary, and Jackson). Perhaps Prince traveled to Warner with them.

Although born in the West Indies, Benjamin Darling’s ancestry traces to the Sengal-Gambia region of Africa. Much of his story is unclear, and legend surrounds his name. It is said that he rescued the man he was enslaved to when their boat was shipwrecked, and, for his loyalty, was awarded his freedom. Another story contends Darling escaped slavery. How he came to the Phippsburg area of Maine is not known. However, he was known there as “sturdy, industrious” and “with many staunch friends.”

On May 26, 1926, Portsmouth’s Elizabeth Ann Virgil became the first African American to graduate from the University of New Hampshire, where she majored in home economics and was active in several music clubs including the Treble Clefs, a group she helped to found.